Last updated: March 14, 2021

Felix, Michael and Rosa emigrate to the United States

On May 19, 1893 Felice Cipolla, soon to be known as Felix Cipollo, arrived in New York on board the S.S. Alesia from Naples, Italy at age 16 by my calculations (15 according to the manifest). He didn't journey alone. Felix traveled with his sister Rosa (age 19) and her husband Vincenzo Crusco (age 21). The ship's records captured her has "Rosa Moglie." Moglie is Italian for "wife."

A copper-hued Statue of Liberty, then just six years old, would have greeted the 983 passengers of the S.S. Alesia as they arrived in New York harbor in 1893. Ellis Island, having opened just 17 months prior, would have been the first stop for them. The Ellis Island structures that greeted Felix, Rosa and Vincenzo predate the now familiar red brick buildings that welcomed millions of immigrants in the 1900s. In 1893 the main immigration building was a wooden structure built of Georgia Pine and covered with a slate roof. The main building was a two story building that measured about 400 feet long and 150 feet wide. The registry room, measuring 200 feet by 100 feet was the largest and most impressive with a fifty-six foot vaulted ceiling. According to one researcher, "Twelve narrow aisles, divided by iron bars, channeled new arrivals to be examined by doctors at the front of the room." This structure would burn down in June 1897 and be replaced by the structure that stands today. Sadly, many records were lost in the fire.

While we will never know exactly what compelled Felix, Rosa and Vincenzo to depart Italy to start a new life in America, it is likely that they, like other Italians of that era, were fleeing the poor and uncertain economic and political environment of Italy (Read about Italian immigration to Pennsylvania) Each was labeled as a "peasant" on the ship's manifest. However, from an economic opportunity perspective, the timing of emigration from Italy to the United States could have been better. Just weeks after their arrival, the Panic of 1893 struck. The United States entered a severe and unprecedented economic depression that would last until 1898. President Grover Cleveland, in office starting March 1893, two months prior two Felix's arrival, was not able to prevent thousands of businesses from closing, leaving millions unemployed.

According to the immigration records for the Alesia, neither Felix, Rosa nor Vincenzo had the ability to read or write when then arrived. The task in front of them must have appeared daunting. Fortunately, they would find communal support and help build Philadelphia's own "Little Italy". The Alesia's manifest even indicates that they weren't the sole immigrants from Muro Lucano that were headed to Philadelphia. It is quite possible that they had family and friends with roots established in Philadelphia when they arrived.

On November 18, 1898, almost five years after Felix and Rosa arrived in the United States, their brother Michele Cipolla (later known as Michael Cipollo) arrived on board the Alsatia. He was 15 years old and reportedly could read and write. He listed his occupation as "carpenter." Michael carried $4 with him and indicated that he was going to visit his brother "Felice" in Philadelphia. There is no indication on the manifest that he traveled with anyone else, but given his age, that seems like a possibility.

Felix marries Domenica

The 1900s ushered in a new era for Felix Cipollo. On Thursday, April 3, 1902 Felix Cipollo married Domenica D'Agrosa at Our Lady of Good Council at 8th and Christian Streets in Philadelphia. (Note: The parish closed in 1932). Father Angelo Caruso presided as 25 year-old Felix married 20 year-old Domenica. There is a photo of a young Domenica that I believe could be from this time period. On the marriage license she is identified as "Lagroso". For reasons that are unclear (and will probably remain shrouded in mystery) the D'Agrosa family surname transformed over time. You will sometimes find Domemica's family referred to as Lagrossa, Lagrosa, De Grossa, and Dagrosa.

We can say definitively that Domenica, who was known to many as "Minnie", was born in Marisco Nuovo, Italy, on May 28, 1881 to Francesco Savario D'Agrosa (Born 30 August 1836) and Annuziata Votta, also known as "Nunziah" and "Nunziata" (Born 23 Nov 1845). Her father is often identified as Saverio even those "Franceso" part of his given name in official Italian records. He was the son of Rosa Pasquarelli and Donato D'Agrosa. They were a farming family.

Domenica had at least three sisters: Peppina (also found as Giuseppina, Josephenia and finally Josephine) (Born 21 May 1876), Agostina (also found as Augustina and Augustine) (Born ~1875) and Carmela (also found as Millie) (Born 25 Aug 1887). Domenica also had two brothers, Donato (Born 23 May 1868) and Gianurio (Born 22 Jan 1871). All three sisters are known to have moved to Philadelphia. Only Carmela did not marry. To date, nothing has been found to indicate Domenica's brothers moved here. In the 1900 census Nunziah says that she has five living children.

Dates surrounding the D'Agrosa (Lagrossa) family emigration to the United States are muddled. To date only one official emigration document has been found. It references Francesco Saverio D'Agroso arriving on 13 January 1898, on the California and headed for Philadelphia from Naples. This must be one of at least two trips he made from Italy to the US since he is also found living in Philadelphia in an 1890 almanac under the name "Saverio De Grossa" which I'm confident is him given the address and name.

One unsourced family document (probably derived from oral family tradition) says Domenica arrived when she was 9, which would mean 1890. According to the 1900 census Domenica and her parents arrived in the United States in 1882, eleven years before the Cipollo family and before Ellis Island was opened. If true, that date didn't apply to the entire family because we know the youngest child, Carmela, was born in Italy in 1887. Other census documents suggest they could have arrived in 1888 or 1892. In her May 1892 her naturalization papers her sister Agostina (by then known as Augustina Fortunato) recorded 4 June 1887 as her arrival date in this country.

It is unclear what accounts for all the different dates. Maybe it is a reflection of multiple trips to and from Italy and the family coming in small waves. That was not an entirely uncommon practice for Italian-American immigrants as many did not intend to stay here permanently as they hoped circumstances at home would improve. Of course it could simply be errors by census takers or poor communication by the family. There is ample evidence that they lacked formal education and had little if any literacy. Further research is needed before we can reach any firm conclusions. If we take the earliest possible arrival date as true, Domenica would have been no more than a year old when she arrived in the United States.

Oddly enough, Millie, the youngest member of the family does not appear on the 1900 census for the family. Where was she? Depending on the immigration dates for the family, it is possible that she had not yet arrived in the United States from Italy or she was part of some back-n-forth movement and was possibly in Italy with family.

Making a home in Philadelphia

Like Italian immigrants in other urban centers, the Italians in Philadelphia formed their own "Little Italies" throughout the city. The 1890 census, which took place three years before Felix arrived, counted the Italian-born population of Philadelphia at 6,799. The official Italian-born population grew to 17,830 by 1900 and to 45,308 by 1910. However, when you include Americans born of Italian parentage, the population was about 77,000 by 1910. The largest concentration of Italians was in South Philadelphia, an area centered around 8th & Christian, near the now-famous Italian Market on 9th Street.

We don't know exactly where Felix lived when he arrived in Philadelphia. No 1900 census has been found and no Philadelphia city directories list him or his sister Rosa Crusco and her husband Vincenzo (with whom Felix might have lived early on).

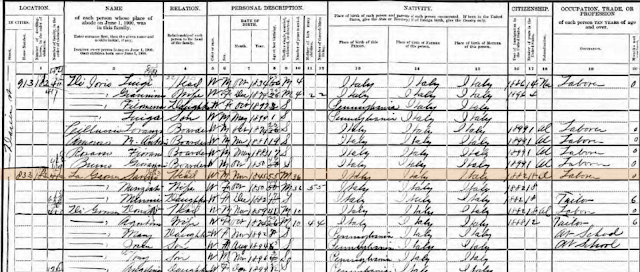

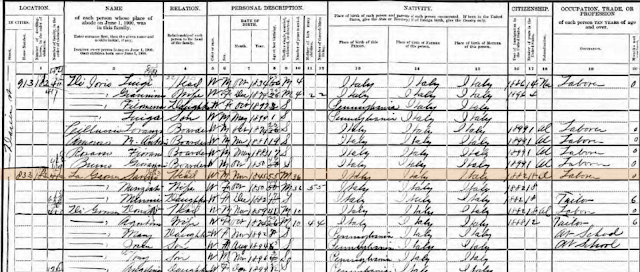

However, Felix's future wife Domenica was definitely living within South Philadelphia's "Little Italy" at 833 Montrose Street with her parents in 1900. This address is right around the corner from the Italian Market. Domenica's father, Saverio, was employed as a "laborer" and Domenica was a "tailor" at that time.

Three other Italian families also resided in the building. Among them were members of the DiGrossa family (sometimes referred to as the DeGrossa or DaGrossa family). This is where things get really confusing. This family was one that Domenica's sister Agostina married into. Agostina (age 25) was living with her husband of 10 years, Donata DiGrossa (age 40) and their four Pennsylvania-born children, Mary (age 7), Josie (spelling?) (age 5), Tony (age 3), and Angelina (less than a year old). Given what we know about Agostina's original surname (d'Agrosa) and the surname of her husband "DiGrossa" and factoring in the likely roots of that family, it seems like their might have been a family connection going back to Italy. This nuance needs to be researched further.

|

| 1900 Census with the d'Agrosa (AKA LaGrossa) family at 833 Montrose in Philadelphia |

When Felix and Domenica applied for their marriage license in 1902, Felix indicated that he was living at 829 Montrose Street, just a few doors down from his future in-laws. This same residence is captured on Felix's Petition for Naturalization papers in 1903. Thus, the first place Felix and Domenica called home together was 829 Montrose Street (Note: It does not appear as though there is a home at this address today).

The world they lived in

What was the world around Felix and Domenica like when then they married in 1902? By some accounts, the Italian Market, an area that anchors the modern image of the South Philadelphia, began to take shape in the mid-to-late 1880s, just a few years before Felix arrived. However, some researchers have found that the real transformation of 9th street didn't start to take hold until 1900 with the introduction of pushcarts by Sicilians along the once purely residential street. Felix and Domenica might have found themselves shopping for food and dry goods at those very pushcarts or possibly among the Italian grocery shops along Seventh and Eighth streets from Fitzwater to Christian. Regardless, they were a part of a changing landscape, one that saw an expansion of Italian influence in South Philadelphia.

Like other Italian immigrants to America, Felix and Domenica were not walled-off from other ethnic communities. The city itself was ethnically diverse in 1902. Even Philadelphia's "Little Italy" wasn't purely Italian. The area was formerly known as "Irish Town" and you can see evidence of the Irish legacy in the census reports. Italians only began to outnumber the Irish in the area starting in the 1890s. While no Irish neighbors are found on Felix and Domenica's block of Montrose Street near the time of their marriage (ethnic Italians dominated), the same can't be said for members of their family. Census records show both Irish neighbors and German neighbors living in close proximity to the extended family who lived just a few blocks away from Felix and Domenica. In 1910 Felix and Domenica's neighbors on Kauffman Street were largely "Russo-Yiddish" speakers, illustrating that they were indeed part of an ethnic melting pot. We can only imagine the sounds of the conversations between them.

The setting for Felix and Domenica's first year together as husband and wife in South Philadelphia is the bigger stage of Philadelphia and even the United States in 1902. At the time of their marriage, Theodore Roosevelt dominated the national scene. He assumed the Presidency a year prior following the assassination of President McKinley. Things that drew President Roosevelt's attention included plans for the Panama Canal, unfolding tensions in the Philippines (the US took control of the islands from Spain following 1898 Spanish-American War) and a coal strike in Eastern Pennsylvania that threatened home heating fuel supplies for cities like Philadelphia.

Within the city of Philadelphia, things looked a lot different than the do today. The newly constructed City Hall (completed in 1901) stood as the world’s tallest habitable building in 1902. That prestige seems fitting given the city’s position as the country’s 3rd largest city with 1.3 million residents at the time. Plans for another iconic structure in the city, today’s popular Philadelphia Museum of Art, wouldn’t be submitted for several more years. In its place at Fairmount was a reservoir fed by the still standing Fairmount Waterworks.

Many of the daily challenges of city dwellers were similar to those encountered today, yet different in notable ways. For example, current day city living concerns regarding automobile traffic would have been alien. Cars were practically nonexistent (only about 8,000 in the country in 1900). Instead, city streets would have been crowed with the 50,000 plus resident horses (plus those stabled outside the city and traveled-in) that moved freight, provided emergency services and public transport (horse-drawn trolleys). Smells of manure would have been present, not smells truck diesel and car fumes. Of course that scene would change over time, and within 6 years of their marriage Felix and Domenica had the opportunity to take advantage Philadelphia's first subway and elevated train line, the Frankford-Market line (seen here under construction). Today's city dwellers still travel those rails.

It is fun to think that maybe Felix and Domenica were taken with modern Philadelphia's baseball obsession. The Philadelphia Athletics of 1902 drew over 400,000 fans as they took first place in the upstart American League from their home at Columbia Park in North Philadelphia. The Phillies didn't fair as well, finishing seventh in the more established National League where they played from the Baker Bowl on North Broad Street. Oddly enough there were also two National Football League Teams in Philadelphia (it was a 3 team league) who battled each other for the hearts and dollars of the citizens. They were also known as the Philadelphia Athletics and Philadelphia Phillies!

I'm not sure how often Felix and Domenica were able to relax and enjoy the city and surrounding countryside. There is one photo of them in their bathing suits in their younger years that suggests that made a trip to the beach, lake or pool to have some fun at some point. Today's Philadelphian's can surely relate to the call of cool water in the summer. Thankfully, bathing suit styles have changed dramatically in the last 100+ years.

We'll never know the daily things that consumed their time and thoughts, but can try understand their times. More research is needed to paint a better picture.

The American dream

The marriage license for Felix and Domenica captures their occupations at 1902. Domenica worked as a "tailoress" and Felix as a "news dealer." Gopsill's 1902 Philadelphia City Directory indicates that the "news dealer" business was based at 945 Ridge Avenue (Note: Joseph Gillelaud, the person who served as a witness for Felix's Petitition of Naturalization was a resident of 911 Ridge Ave.) Today, 945 Ridge Ave. is near the base of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Back in 1902, the bridge wasn't part of the landscape. Construction began almost two decades later in 1919 (and was completed in 1926). Domenica's occupation was typical for Italian women at that time. By 1910 half of the women working in the clothing industry in Philadelphia were Italian.

According to information found in city directories and census documents, the extended family of Felix and Domenica held a variety of jobs such as "presser" (likely a job involving pressing fabric), "laborer," "music," "bartender" and more in the early 1900s. Savario LaGrossa, Felix's father-in-law, is found to be engaged in the "Liquor" business in 1902. "Saveri", as the directory calls him, appears to have been working at 1211 S. 8th Street, just around the corner from the now-famous Pat's and Geno's cheesesteak establishments (of course those would be years away from taking root). It seems possible that Saverio's experience in the liquor business would prove beneficial to Felix in a later business venture. By 1904 Felix was involved in the "liquor" business too, according to a city directory. Felix would grow this business at 811 Passyunk Avenue and regularly identify himself as a "saloon keeper" at this address in various documents. Other extended family members might have played a role in his saloon enterprise. For example, Charles Cianciarulo, brother of his brother-in-law Domenick Ciancurlo (Domenica's sister Josephine's husband) is sometimes found as a "bartender" or otherwise engaged in the liquor business on Passyunk Ave. No house number is given, but could this have been Felix's business?

By 1910 Felix and Domenica moved to 526 Kauffman Street, just around the corner from his saloon business on Passyunk Avenue. From this address their family would begin to grow. Eventually they would move the family to Passyunk Avenue. By the 1930 census Felix owned the properties at 801 - 807 Passyunk Ave. (valued at $60k in the census, the equivalent of $817k in 2012).

No doubt there were many challenges being a "saloon keeper," but probably none bigger than the passing of the 18th Amendment. That amendment to the US Constitution prohibited the manufacture, transportation and sale of alcohol. The prohibition era stretched from 1919 to 1933. The effects of this on Felix's enterprises can be seen in city directories and census documents. In 1923, for example, the city directory records Felix engaging in the sale of "soft drinks" (not liquor!) at 801 Passynunk Ave. The 1930 census indicates that Felix and members of his family were involved in a restaurant and "chicken store," likely on the property he owned on Passyunk Ave. There are photos of Felix that might capture him in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s.

The first generation is born in Philadelphia

Vincenzo and Rosa Crusco

Felix's sister, Rosa likely gave birth to the first Italian-American grandson of Maria Vincenza Cipolla and Luigi Cipolla. Louis Crusco (sometimes known as Lewis) was born to her and Vincenzo Crusco around 1901. The name Louis may have been a nod to Rosa's grandfather, Luigi. Louis would be the only child born to Vincenzo and Rosa.

Felix & Domenica

The first generation of American-born Cipollos began with the arrival of Felix and Domenica's daughter Mary (likely a grandmother's namesake) Cipollo on January 25, 1903. Their family grew quickly during the first decade of the 20th Century. Mary's arrival would be followed by the first Cipollo son, Luigi Cipollo (grandfather's namesake) on August 4, 1904, Samuel Cipollo (possibly an adaptation of Saverio) in 1907, Nancy Cipollo (a likely nod to "Nuziah") on October 12, 1908 and Theresa "Tessie" (a possible nod to her great grandmother) Cipollo (born August 25, 1910). Six more children would arrive in the next decade, many sharing names with aunts and uncles: Rose Cipollo (born November 13, 1912), Susanne Cipollo (born July 15 1915), Josephine Cipollo (born August 20, 1917), Michael Cipollo (August 20, 1919), Louis Cipollo (born June 11, 1922) and Rita Cipollo (born March 12, 1925).

Family losses

Luigi Cipollo, son of Felix and Domenica Cipollo

Unfortunately, amidst this growth in their family Felix and Domenica suffered the loss of their first born son, Luigi, on November 3, 1919. Oral family tradition suggests he might have had a life-long heart ailment and his death certificate (where he is listed as Louis) indicates that he died from Dilatation of the Heart at Presbyterian Hospital. He was 15 years, 3 months and 1 day old when he died. It is worth noting that this time period marked the Great Pandemic in which an especially virulent influenza virus struck, killing an estimated 675,000 Americans, and up to 50 million globally. Over 15,000 Philadelphians were dead from influenza by October 25, 1919. However, nothing in Luigi's death certificate identifies that influenza was a contributing factor in his death.

Luigi was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon following a mass at St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi church at 8th and Montrose. This parish was set-up in 1852 to serve the Italian immigrant population. It seems likely that the loss of Luigi influenced Felix and Domenica to name the first son born to them after Luigi's death, "Louis." It is curious to see that Luigi was actually referred to as "Louis" in his Philadelphia Inquirer death notice.

Michael Cipollo, brother of Felix Cipollo

No records have been found thus far to indicate where Felix and Rosa's youngest brother Michael was living and working during the first decade of the 1900s. However, it is known that Michael Cipollo married Margaret DeVico. According to the 1910 census, Margaret was was born in Pennsylvania to Italian immigrants. They were married about 1906 when she was about 17 and he was about 22. In 1910 they lived at 1340 9th Street, Philadelphia. This is the same address of his sister Rosa and Vincenzo Crusco for that period. Michael worked as a carpenter according to census records and there are even solicitations for work by him in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Michael and Margaret eventually moved to Collingswood, New Jersey where sadly Michael would die at age 38 on June 9, 1921. Michael and Margaret did not have any children. He was buried at the same cemetery as his nephew Luigi, who died less than two years earlier.

Maria Vincenza Cipollo, mother of Felix Cipollo

On March 20, 1935 the mother of Felix Cipollo, Michael Cipollo and Rosa Cipollo Crusco passed away in Philadelphia. She was daughter of Pasqualle Trotto and Marria Teresa Di Canio. It is thought that her husband Luigi likely passed away in Muro Lucano, Italy prior to her arrival in the United States. She was 77 years old. She was laid to rest in Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon.

Saverio LaGrossa and Annunizata LaGrossa

Saverio LaGrossa, the father of Domenica LaGrossa and father-in-law of Felix Cipollo passed away on December 22, 1923. He was 72 years, 4 months and 18 days old. His wife, Annuziata ("Nunziah") would survive him by more than twelve years, passing away in April 1935, just a month after the passing of Maria Vincenza Cipollo. Both Saverio and Annuziata resided at 1304 Federal Street in Philadelphia when they passed. It appears Angelo Cianciarulo, Annuziata's grandson and the informant of her death on record, was living with her at the time. Saverio and Nunziah are buried in Holy Cross Cemetery with other members of their family. You can see a photo of Nunziah in her later years alongside her daughter Domenica.

Felix Cipollo

A string of family losses hit hard on April 9, 1936 when Felix Cipollo fell victim to heart problems and passed away. He was 59 years old. This was just a year after his mother and mother-in-law had passed. This had to be emotionally devasting to Domenica LaGrossa, his spouse of about 32 years, and their children. The family was not only reeling from the loss of loved ones, but likely the negative economic impact of The Great Depression on family fortunes. The combined economic impact of this may be seen in the 1940 Census where it is evident that the family lost properties (they now rented 807 Passyunk instead of owning 801-807). By 1940 there is no sign that the family still owned any businesses, and instead two older children, Josephine and Michael are working in department stores as sales clerks.

Felix was interred in Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania alongside family and friends.

Vincenzo Crusco and Rosamarie (Rosa) Cipolla Crusco

Rosa, the only known sister of Felix and Michael Cipollo outlived her siblings by more than twenty years. On March 18, 1957 at the age of 77 Rosa passed away. At that time she was a resident of 1031 Morris St. in Philadelphia. By that time she was the grandmother of 7 and great-grandmother of 9. All her grandchildren descended through her only son Lewis (also known as Louis). Following a mass at St. Nicolas Church she was laid to rest in Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, PA. Her husband Vincenzo Crusco outlived her by a almost three years, passing away at age 91 in November 1960. Today he is buried alongside Rosa, his son Lewis and other members of his family.

Domenica "Minni" LaGrossa CipolloThe wife of Felix Cipollo lived until April 21, 1972, having outlived her husband by 36 years, passing away at age 90. Like many members of her extended family she was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery. Today, many families three and four generations later trace their roots back to Domenica and Felix. Many of those families took began to blossom well before she passed away. She saw family go off to war, get married and raise their own families. Her longevity allowed her to embrace many grandchildren and grandchildren.

The first generation marries, has children

There was no shortage of heartache from the loss of loved ones in the first third of the 20th Century, but there also joy. The next chapter of Cipollo family history look more closely at the first generation born in the United States.